Today's Wall Street Journal has an article on ID in college classrooms today.

AMES, Iowa -- With a magician's flourish, Thomas Ingebritsen pulled six mousetraps from a shopping bag and handed them out to students in his "God and Science" seminar. At his instruction, they removed one component -- either the spring, hammer or holding bar -- from each mousetrap. They then tested the traps, which all failed to snap.

"Is the mousetrap irreducibly complex?" the Iowa State University molecular biologist asked the class.

"Yes, definitely," said Jason Mueller, a junior biochemistry major wearing a cross around his neck.

That's the answer Mr. Ingebritsen was looking for. He was using the mousetrap to support the antievolution doctrine known as intelligent design. Like a mousetrap, the associate professor suggested, living cells are "irreducibly complex" -- they can't fulfill their functions without all of their parts. Hence, they could not have evolved bit by bit through natural selection but must have been devised by a creator.

"This is the closest to a science class on campus where anybody's going to talk about intelligent design," the fatherly looking associate professor told his class. "At least for now."

Overshadowed by attacks on evolution in high-school science curricula, intelligent design is gaining a precarious and hotly contested foothold in American higher education. Intelligent-design courses have cropped up at the state universities of Minnesota, Georgia and New Mexico, as well as Iowa State, and at private institutions such as Wake Forest and Carnegie Mellon. Most of the courses, like Mr. Ingebritsen's, are small seminars that don't count for science credit. Many colleges have also hosted lectures by advocates of the doctrine

*groan*

At the end of the article, they present one of Ingebritsen's tactics:

On a brisk Thursday in October, following the mousetrap gambit, Mr. Ingebritsen displayed diagrams on an overhead projector of "irreducibly complex" structures such as bacterial flagellum, the motor that helps bacteria move about. The flagellum, he said, constitutes strong evidence for intelligent design. One student, Mary West, disputed this conclusion. "These systems could have arisen through natural selection," the senior said, citing the pro-evolution textbook.

"That doesn't explain this system," Mr. Ingebritsen answered. "You're a scientist. How did the flagellum evolve? Do you have a compelling argument for how it came into being?"

Ms. West looked down, avoiding his eye. "Nope," she muttered. The textbook, "Finding Darwin's God," by Kenneth Miller, a biology professor at Brown University, asserts that a flagellum isn't irreducibly complex because it can function to some degree even without all of its parts. This suggests to evolutionists that the flagellum could have developed over time, adding parts that made it work better.

During a class break, Ms. West says that Mr. Ingebritsen often puts her on the spot. "He knows I'm not religious," she says. "In the beginning, we talked about our religious philosophy. Everyone else in the class is some sort of a Christian. I'm not." The course helps her understand "the arguments on the other side," she adds, but she would like to see Mr. Ingebritsen co-teach it with a proponent of evolution.

Ms. West and other honors students will have a chance to hear the opposing viewpoint next semester. Counter-programming against Mr. Ingebritsen, three faculty members are preparing a seminar titled: "The Nature of Science: Why the Overwhelming Consensus of Science is that Intelligent Design is not Good Science."

I think that's a *course,* not a one-time, hour-long seminar, if I'm not mistaken. Or at least, a similar one was/is in the works there. Additionally, for those of you who are in Iowa, there also will be a seminar on Feb. 2nd at ISU:

Why Intelligent Design Is Not Science - Robert M. Hazen 02 Feb 2006, 8:00 PM @ Sun Room, Memorial Union - Robert M. Hazen is the Clarence Robinson Professor of Earth Science at George Mason University, and a scientist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington's Geophysical Laboratory. He received his M.S. in geology from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and his Ph.D. in Earth Sciences from HarvardUniversity. Dr. Hazen is the author of over 240 articles and 16 books, including the most recent Genesis: The Scientific Quest for Life's Origin; Why Aren't Black Holes Black? and the best-selling Science Matters: Achieving Scientific Literacy, which he co-authored with James Trefil. Dr. Hazen has recorded the acclaimed lecture series, The Joy of Science, with the Teaching Company (www.Teach12.com), which provides a fresh and definitive overview of all the physical and biological sciences.

Finally, again for those of you in the Hawkeye State, the Iowa Citizens for Science group now has a website: http://www.iowascience.org. It's still a bit rough, but I'll be updating it with events like these as I find out about them, so keep an eye on it--and drop me an email (iowascience AT gmail DOT com) if you'd like me to add you to the email list for even quicker updates.

Additionally, it was noted that applications are being accepted for

Additionally, it was noted that applications are being accepted for  Have you ever wondered how Kevin Bacon and the lights of fireflies related to malaria and power grids? I know it’s something that’s kept me up many a sleepless night. One word: interconnections.

Have you ever wondered how Kevin Bacon and the lights of fireflies related to malaria and power grids? I know it’s something that’s kept me up many a sleepless night. One word: interconnections. Similarly, Duncan Watts first became interested in the “small world problem”—the idea that all of us are more closely connected than we realize—after watching fireflies flash in synchrony, and wondering how they accomplished that. What Watts, Strogatz, Milgram, and others were investigating boiled down to a series of links in a network—hubs and connectors. As Watts and Strogatz showed in their 1998 paper, all it took to make a "small world" from a regular network was the addition of a few "short cuts" (see figure from their paper, above). This elegant and seemingly simple structure of networks explains not only connections between movie stars and

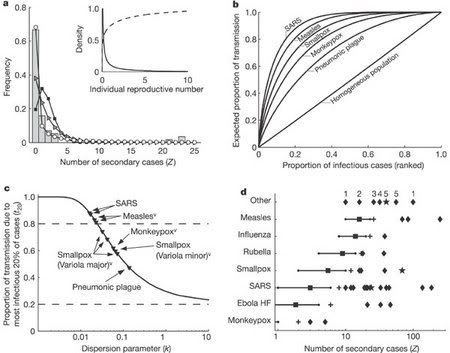

Similarly, Duncan Watts first became interested in the “small world problem”—the idea that all of us are more closely connected than we realize—after watching fireflies flash in synchrony, and wondering how they accomplished that. What Watts, Strogatz, Milgram, and others were investigating boiled down to a series of links in a network—hubs and connectors. As Watts and Strogatz showed in their 1998 paper, all it took to make a "small world" from a regular network was the addition of a few "short cuts" (see figure from their paper, above). This elegant and seemingly simple structure of networks explains not only connections between movie stars and  Early work in this area did not take this difference into account, and assumed that individuals in a population had an equal chance of transmitting the disease. However, reality does not bear this out, leading to the proposal of the "20/80 rule," which suggests that approximately 20% of the most infectious individuals are responsible for 80% of the disease transmission. This was most recently demonstrated by an analysis of the 2003 SARS outbreak (see figure, from MMWR 52(18);405-411), but has also been seen with AIDS and other STDs. With AIDS, we recognize that "core groups" of infected individuals are often responsible for large outbreaks of disease. What we see when we examine this graphically is a "small world" network: a series of hubs and connectors, with the largest hubs—-termed "superspreaders" (the numbered dots in the picture above)--responsible for a disproportionately large number of secondary cases. This may be due to the fact that the superspreaders simply have a higher number of contacts; they may have a co-infection that leads to increased pathogen shedding, meaning the contacts they have are more efficiently exposed; they may have an undiagnosed illness, leading to an extended period of transmission; or they may have a combination of the above. For example, imagine a sex worker with both HIV and a secondary STD, such as gonorrhea. By virtue of her occupation, she will be in contact with a large number of individuals. HIV may lead to an increase in bacterial load, exposing her clients to a larger dose of N. gonorrhea than the "average" infected person; and her lack of health care means she has been treated for neither STD—potentially spreading both for years, until she is too sick to continue working. In this case, there are multiple explanations for why she would be a superspreader.

Early work in this area did not take this difference into account, and assumed that individuals in a population had an equal chance of transmitting the disease. However, reality does not bear this out, leading to the proposal of the "20/80 rule," which suggests that approximately 20% of the most infectious individuals are responsible for 80% of the disease transmission. This was most recently demonstrated by an analysis of the 2003 SARS outbreak (see figure, from MMWR 52(18);405-411), but has also been seen with AIDS and other STDs. With AIDS, we recognize that "core groups" of infected individuals are often responsible for large outbreaks of disease. What we see when we examine this graphically is a "small world" network: a series of hubs and connectors, with the largest hubs—-termed "superspreaders" (the numbered dots in the picture above)--responsible for a disproportionately large number of secondary cases. This may be due to the fact that the superspreaders simply have a higher number of contacts; they may have a co-infection that leads to increased pathogen shedding, meaning the contacts they have are more efficiently exposed; they may have an undiagnosed illness, leading to an extended period of transmission; or they may have a combination of the above. For example, imagine a sex worker with both HIV and a secondary STD, such as gonorrhea. By virtue of her occupation, she will be in contact with a large number of individuals. HIV may lead to an increase in bacterial load, exposing her clients to a larger dose of N. gonorrhea than the "average" infected person; and her lack of health care means she has been treated for neither STD—potentially spreading both for years, until she is too sick to continue working. In this case, there are multiple explanations for why she would be a superspreader.

I mentioned a real "microbial machine" in

I mentioned a real "microbial machine" in

I discussed

I discussed

Vidal, Hedges, and other researchers report this and other discoveries about the early evolution of the venom system in lizards and snakes in a paper led by Bryan G. Fry, of the University of Melbourne in Australia, published in the current issue of the journal Nature. "It's a really startling thing that so many supposedly harmless lizards actually are venomous," Vidal comments, "but their sharing of this characteristic makes sense now that our genetic studies have shown how closely they are related."

Vidal, Hedges, and other researchers report this and other discoveries about the early evolution of the venom system in lizards and snakes in a paper led by Bryan G. Fry, of the University of Melbourne in Australia, published in the current issue of the journal Nature. "It's a really startling thing that so many supposedly harmless lizards actually are venomous," Vidal comments, "but their sharing of this characteristic makes sense now that our genetic studies have shown how closely they are related." Carl Zimmer has a post today about

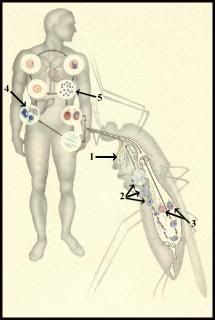

Carl Zimmer has a post today about  troops on both sides stationed in the south suffered more than a million cases of the disease. Indeed, malaria was endemic in the southern United States until the 1940s, and continues to be a problem in the U.S. due to "imported" cases. Despite this huge burden of disease, to date, there has been no successful malaria vaccine. This is largely due to problems that arise in trying to target an organism with an extremely complex life cycle (see image, left). 1. Sporozoites in salivary gland. 2. Oöcysts in stomach wall. 3. Male and female gametocytes. 4. Liver phase. 5. Release of merozoites from liver. These enter red cells where both sexual and asexual cycles continue. As you can see, it's a bit of a mess, with different protozoal antigens being expressed at different times throughout the life cycle. What do you target? Which are the most important for immunity?

troops on both sides stationed in the south suffered more than a million cases of the disease. Indeed, malaria was endemic in the southern United States until the 1940s, and continues to be a problem in the U.S. due to "imported" cases. Despite this huge burden of disease, to date, there has been no successful malaria vaccine. This is largely due to problems that arise in trying to target an organism with an extremely complex life cycle (see image, left). 1. Sporozoites in salivary gland. 2. Oöcysts in stomach wall. 3. Male and female gametocytes. 4. Liver phase. 5. Release of merozoites from liver. These enter red cells where both sexual and asexual cycles continue. As you can see, it's a bit of a mess, with different protozoal antigens being expressed at different times throughout the life cycle. What do you target? Which are the most important for immunity? The last recorded kill of a wild thylacine was recorded in 1930, and the last one captured live was caught in 1933, but died the same year in the Hobart zoo. Since then, the animal has become somewhat of a legend. A sighting was reported in western Australia in the 1980s, but has not been confirmed, and it is assumed to be extinct. However, as mentioned above, attempts have been made in recent years to clone the animal. At least 3 different animals are known to be preserved in ethanol in collections in Australia, and DNA has been extracted. Currently, it seems that the cloning project

The last recorded kill of a wild thylacine was recorded in 1930, and the last one captured live was caught in 1933, but died the same year in the Hobart zoo. Since then, the animal has become somewhat of a legend. A sighting was reported in western Australia in the 1980s, but has not been confirmed, and it is assumed to be extinct. However, as mentioned above, attempts have been made in recent years to clone the animal. At least 3 different animals are known to be preserved in ethanol in collections in Australia, and DNA has been extracted. Currently, it seems that the cloning project  I grew up in the middle of vast swaths of northwestern Ohio farmland. My dad, the youngest of 13 kids, was raised on a farm, most of my uncles still farm to some extent, and collecting eggs and shearing sheep was something I got to do regularly as a kid on visits to Grandma's house. But I'd honestly never heard of

I grew up in the middle of vast swaths of northwestern Ohio farmland. My dad, the youngest of 13 kids, was raised on a farm, most of my uncles still farm to some extent, and collecting eggs and shearing sheep was something I got to do regularly as a kid on visits to Grandma's house. But I'd honestly never heard of

Resistance to antibiotics has been a concern of scientists almost since their widespread use began. In a 1945 interview with the New York Times, Alexander Fleming himself warned that the misuse of penicillin could lead to selection of resistant forms of bacteria, and indeed, he’d already derived such strains in the lab by varying doses of penicillin the bacteria were subjected to. A short 5 years later, several hospitals had reported that a majority of their Staph isolates were, as predicted, resistant to penicillin. This decline in effectiveness has led to a search for new sources and kinds of antimicrobial agents. One strategy involves going back to a decades-old approach researched by Soviet scientists: phage therapy. Here, they pit one microbe directly against another, using viruses called bacteriophage to infect, and kill, pathogenic bacteria.

Resistance to antibiotics has been a concern of scientists almost since their widespread use began. In a 1945 interview with the New York Times, Alexander Fleming himself warned that the misuse of penicillin could lead to selection of resistant forms of bacteria, and indeed, he’d already derived such strains in the lab by varying doses of penicillin the bacteria were subjected to. A short 5 years later, several hospitals had reported that a majority of their Staph isolates were, as predicted, resistant to penicillin. This decline in effectiveness has led to a search for new sources and kinds of antimicrobial agents. One strategy involves going back to a decades-old approach researched by Soviet scientists: phage therapy. Here, they pit one microbe directly against another, using viruses called bacteriophage to infect, and kill, pathogenic bacteria.