New malaria vaccine shows promise

Malaria is one of the world's leading infectious killers. World-wide, almost 40% of the world's population is at risk of acquiring this disease--many of them in poor countries with limited resources to control the disease. Each year, malaria causes 300-500 million infections, and up to 3 million deaths--about 5000 Africans die of the disease every day; one child succumbs every 30 seconds. Mosquito-borne, simple devices (such as mosquito nets over beds) have been shown to drastically decrease the incidence of disease. Though these only cost a few dollars each, many in developing countries lack the resources to purchase them. Additionally, evolution, as we often see, has caused both the parasites that cause the disease (one of four species of Plasmodium) and the mosquitoes that transmit it (Anopheles species) to become resistant to our efforts to stop them. The parasites have developed high levels of resistance to many of the anti-malarial drugs, and many insecticides are of little use in controlling the mosquito population due to a similar phenomenon.

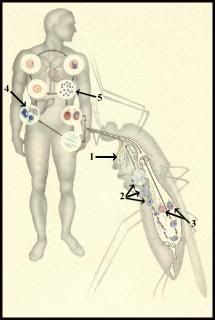

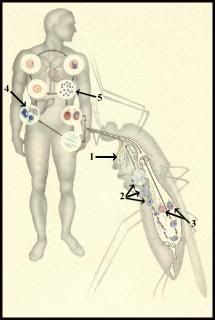

Malaria is an ancient disease. Descriptions of malarial symptoms exist in Chinese literature dating back almost 5000 years. The name itself comes from 16th century Italy, meaning "bad air" (the assumed cause at that time). The disease used to be rampant in the United States. During the U.S. Civil war, troops on both sides stationed in the south suffered more than a million cases of the disease. Indeed, malaria was endemic in the southern United States until the 1940s, and continues to be a problem in the U.S. due to "imported" cases. Despite this huge burden of disease, to date, there has been no successful malaria vaccine. This is largely due to problems that arise in trying to target an organism with an extremely complex life cycle (see image, left). 1. Sporozoites in salivary gland. 2. Oöcysts in stomach wall. 3. Male and female gametocytes. 4. Liver phase. 5. Release of merozoites from liver. These enter red cells where both sexual and asexual cycles continue. As you can see, it's a bit of a mess, with different protozoal antigens being expressed at different times throughout the life cycle. What do you target? Which are the most important for immunity?

troops on both sides stationed in the south suffered more than a million cases of the disease. Indeed, malaria was endemic in the southern United States until the 1940s, and continues to be a problem in the U.S. due to "imported" cases. Despite this huge burden of disease, to date, there has been no successful malaria vaccine. This is largely due to problems that arise in trying to target an organism with an extremely complex life cycle (see image, left). 1. Sporozoites in salivary gland. 2. Oöcysts in stomach wall. 3. Male and female gametocytes. 4. Liver phase. 5. Release of merozoites from liver. These enter red cells where both sexual and asexual cycles continue. As you can see, it's a bit of a mess, with different protozoal antigens being expressed at different times throughout the life cycle. What do you target? Which are the most important for immunity?

A new study may have cracked that question. Led by Pierre Druilhe of the Pasteur Institute (link to journal article), investigators focused on a malaria protein--merozoite surface protein 3 (MSP-3)--that prior research had identified as the focus of the immune systems of adults who had proven resistant to the disease.

They didn't challenge the volunteers with Plasmodium infection to put the nail in the coffin, but they did test it in humanized mice, where it was highly effective. Additionally, they tested the blood of immunized volunteers a year after vaccination, and it still was effective in neutralizing the pathogen. A long-lasting vaccine would be critical, since as mentioned above, resources in these countries are scarce, and frequent boosters would be unlikely.

Malaria vaccine research has also recently been given a "booster" of its own, in the form of a $258 million pledge by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. About 40% of that donation is earmarked for vaccine research. However, while the news seems to be positive in the fight against malaria, we want to use caution. I recently linked a discussion on the evolution of avian influenza virulence. Similarly, a group of scientists published a paper last year suggesting that inadequate vaccines could increase malarial virulence:

Malaria is an ancient disease. Descriptions of malarial symptoms exist in Chinese literature dating back almost 5000 years. The name itself comes from 16th century Italy, meaning "bad air" (the assumed cause at that time). The disease used to be rampant in the United States. During the U.S. Civil war,

troops on both sides stationed in the south suffered more than a million cases of the disease. Indeed, malaria was endemic in the southern United States until the 1940s, and continues to be a problem in the U.S. due to "imported" cases. Despite this huge burden of disease, to date, there has been no successful malaria vaccine. This is largely due to problems that arise in trying to target an organism with an extremely complex life cycle (see image, left). 1. Sporozoites in salivary gland. 2. Oöcysts in stomach wall. 3. Male and female gametocytes. 4. Liver phase. 5. Release of merozoites from liver. These enter red cells where both sexual and asexual cycles continue. As you can see, it's a bit of a mess, with different protozoal antigens being expressed at different times throughout the life cycle. What do you target? Which are the most important for immunity?

troops on both sides stationed in the south suffered more than a million cases of the disease. Indeed, malaria was endemic in the southern United States until the 1940s, and continues to be a problem in the U.S. due to "imported" cases. Despite this huge burden of disease, to date, there has been no successful malaria vaccine. This is largely due to problems that arise in trying to target an organism with an extremely complex life cycle (see image, left). 1. Sporozoites in salivary gland. 2. Oöcysts in stomach wall. 3. Male and female gametocytes. 4. Liver phase. 5. Release of merozoites from liver. These enter red cells where both sexual and asexual cycles continue. As you can see, it's a bit of a mess, with different protozoal antigens being expressed at different times throughout the life cycle. What do you target? Which are the most important for immunity?A new study may have cracked that question. Led by Pierre Druilhe of the Pasteur Institute (link to journal article), investigators focused on a malaria protein--merozoite surface protein 3 (MSP-3)--that prior research had identified as the focus of the immune systems of adults who had proven resistant to the disease.

The team injected an MSP-3-based vaccine into 30 European volunteers who had never had malaria, readministering it after one month and again after four months. Blood samples were taken one month after each injection. These blood samples were then compared to French blood samples from individuals with no immunity to malaria and African blood samples from people with immunity.

Nearly every vaccinated sample produced an immune response to malaria when it was introduced in vitro and 77 percent produced anti-MSP-3 antibodies. Plus, these antibodies proved to be as good at killing the parasite as those from immune adults and, in some cases, better, destroying up to twice as much. "This type of immune response, characteristic of immune adults living in malaria-endemic regions, requires under natural conditions 10 to 15 years of daily exposure to billions of infected red blood cells," Druilhe notes.

They didn't challenge the volunteers with Plasmodium infection to put the nail in the coffin, but they did test it in humanized mice, where it was highly effective. Additionally, they tested the blood of immunized volunteers a year after vaccination, and it still was effective in neutralizing the pathogen. A long-lasting vaccine would be critical, since as mentioned above, resources in these countries are scarce, and frequent boosters would be unlikely.

Malaria vaccine research has also recently been given a "booster" of its own, in the form of a $258 million pledge by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. About 40% of that donation is earmarked for vaccine research. However, while the news seems to be positive in the fight against malaria, we want to use caution. I recently linked a discussion on the evolution of avian influenza virulence. Similarly, a group of scientists published a paper last year suggesting that inadequate vaccines could increase malarial virulence:

Vaccines are designed to protect people by boosting the immune system to kill parasites but, unless a malaria vaccine leads to the death of every single parasite, the ones that survive are likely to be the nastiest.This echoes a 2001 warning in Nature magazine by 2 of the same authors, where they emphasize infection-blocking vaccines, rather than vaccines that target the agent once infection has been established. The Druilhe article doesn't cite either of these studies, so I don't know if that's a concern they'd considered or not. However, since they identified this antigen by screening those in Africa who'd been repeatedly exposed *naturally* and were already immune, it seems likely that any increase in virulence due to partial immunity would have already occurred. Overall, this is some much-needed good news in the fight against this devastating infection.

Initially, the Edinburgh researchers directly injected two groups of mice with infectious parasites - "immunised" mice, which had been exposed to Plasmodium and then treated with the anti-malarial drug, mefloquine, and "naive" mice, which had not. They then transferred parasites via a syringe from host to host 20 times. The parasites thus evolved in the immune or non-immune environments. The parasites that evolved in the immunised mice were more virulent than parasites evolved in the naive mice. Infection was not as severe after transmission through mosquitoes, but the effect was still there. In other words, immunity accelerates the evolution of virulence in malaria, even after mosquito transmission, making them more dangerous to their non-immunised hosts.

Dr. Mackinnon said: "How does immune selection create more virulent pathogens? One possibility is that many parasites die in immunised hosts but those that win "the race to the syringe" - or the mosquito - are probably genetically equipped to stay ahead of the advancing immune system. Since the virulent strains showed no problems transmitting infection to new hosts, it's likely that such strains would spread throughout an immunised population.