Pandemic Influenza awareness week Day 4: 1918 influenza virus reconstructed

I know I said I was going to discuss a bit more about pandemic preparedness today, but I think I'll hold off on that to discuss this story:

This isn't the first time parts of the 1918 flu virus have been "resurrected." Other genes have already been spliced into "modern" influenza viruses, in order to test whether the presence of the 1918 gene increases the virulence potential of the virus. However, this is the first time the entire virus has been re-assembled.

How'd they do it?

Researchers led by Jeffrey Taubenberger have been working on sequencing the 1918 influenza virus for several years. To obtain the virus, they unearthed victims of the pandemic who'd died in a small town called Brevig Mission, Alaska. They obtained one sample from this location. Additionally, Taubenberger is employed at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, which houses an immense collection of tissue samples. 2 lung samples were found in that repository, fixed in formalin, from 1918 flu victims. These three samples have been sequenced and pieced together bit-by-bit, each gene being compared to those from other influenza isolates along the way. It was already known that the 1918 virus was most closely related to the mammalian isolates they examined, but it was the most "avian-like" of all of those. Therefore, they suspected it was an avian virus that had been adapting to mammals for awhile prior to the pandemic. The current research with the whole virus supports this claim.

To get whole virus, the scientists used a process called "reverse genetics." Normally, we have an organism first (bacteria, plant, human, etc.), and want to decipher certain portions of their DNA. In reverse genetics, we start from the nucleotide sequence first, and arrive at the gene products. In this case, plasmids carrying all of the genes to make up the 1918 flu virus were inserted into human kidney cells, which act as the virus factories. The plasmids replicated within the cells, producing the viral proteins. These proteins assembled within the cell, and voila--intact virus.

These viruses were then injected into mice in order to determine the virulence of the virus--and it's a doozy. According to Nature:

The concern

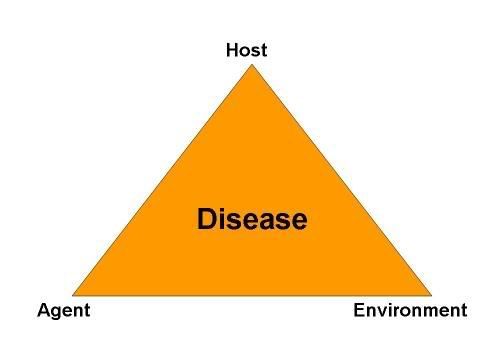

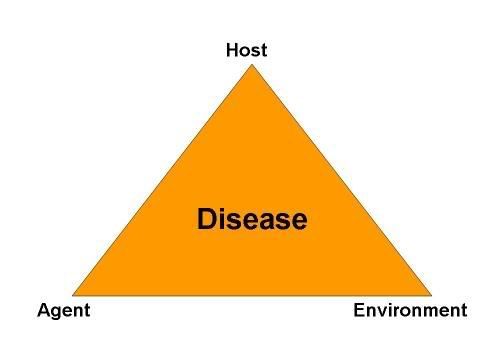

Not surprisingly, many people are concerned about this revelation. They've pointed out that the group has made what is possibly the ideal bioterrorist agent: deadly and highly transmissible. Tumpey et al. counter back that significant precautions were taken, and remain in place regarding storage and handling of the virus. We also need to remember the old causation triangle:

Though the agent may be the same, the host and the environment are much different. The population in 1918 may have been mostly naive to H1N1 serotype viruses, but the current population is not. Indeed, there's an H1N1 serotype virus in the vaccine forumlation for 2005-6, and similar viruses have been used for years. Viruses of this serotype have been circulating for decades, so much of the population should have at least a partial immunity to the 1918 virus. Additionally, one change in the greater "environment" is the production of antiviral drugs. Tamiflu has already been shown to be effective against the 1918 virus. As I mentioned yesterday, the 2 influenza models published showed that Tamiflu could be used to halt the spread of a pandemic virus, if it's given soon enough and if the R0 is low enough. If there is an intentional release by terrorists, or an accidental release due to a lab accident, there should be enough time to isolate cases and provide Tamiflu before it turns into an epidemic situation. Finally, as the 1918 virus isn't out there circulating (and, therefore, evolving) in nature, a "just in case" vaccine could be made. Given the fact that we have a virus out there that is similar in many ways to the 1918 virus, I think the potential benefits outweigh the possible risks at this point in time. I just hope they don't prove me wrong.

Other posts in the series:

Day 1: History of Pandemic Influenza.

Day 2: Our adventures with avian flu.

Day 3: Challenges to pandemic preparedness

More resources on pandemic influenza:

CIDRAP Pandemic influenza news

Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) Pandemic/Avian flu

CDC's site on Avian flu

Flu wiki

It sounds like a sci-fi thriller. For the first time, scientists have made from scratch the Spanish flu virus that killed millions of people in 1918.

Why? To help them understand how to better fend off a future global epidemic from the bird flu spreading in Southeast Asia.

Researchers believe their work offers proof the 1918 flu originated in birds, and provides insights into how it attacked and multiplied in humans. On top of that, this marks the first time an infectious agent behind a historic pandemic has ever been reconstructed.

This isn't the first time parts of the 1918 flu virus have been "resurrected." Other genes have already been spliced into "modern" influenza viruses, in order to test whether the presence of the 1918 gene increases the virulence potential of the virus. However, this is the first time the entire virus has been re-assembled.

How'd they do it?

Researchers led by Jeffrey Taubenberger have been working on sequencing the 1918 influenza virus for several years. To obtain the virus, they unearthed victims of the pandemic who'd died in a small town called Brevig Mission, Alaska. They obtained one sample from this location. Additionally, Taubenberger is employed at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, which houses an immense collection of tissue samples. 2 lung samples were found in that repository, fixed in formalin, from 1918 flu victims. These three samples have been sequenced and pieced together bit-by-bit, each gene being compared to those from other influenza isolates along the way. It was already known that the 1918 virus was most closely related to the mammalian isolates they examined, but it was the most "avian-like" of all of those. Therefore, they suspected it was an avian virus that had been adapting to mammals for awhile prior to the pandemic. The current research with the whole virus supports this claim.

To get whole virus, the scientists used a process called "reverse genetics." Normally, we have an organism first (bacteria, plant, human, etc.), and want to decipher certain portions of their DNA. In reverse genetics, we start from the nucleotide sequence first, and arrive at the gene products. In this case, plasmids carrying all of the genes to make up the 1918 flu virus were inserted into human kidney cells, which act as the virus factories. The plasmids replicated within the cells, producing the viral proteins. These proteins assembled within the cell, and voila--intact virus.

These viruses were then injected into mice in order to determine the virulence of the virus--and it's a doozy. According to Nature:

50 times as many virus particles are released from human lung cells a day after infection with the 1918 virus as are released after exposure to a contemporary strain called the Texas virus. 13% of body weight is lost by mice 2 days after infection with 1918 flu; weight loss is only transient in mice infected with the Texas strain. 39,000 times more virus particles are found in mouse lung tissue 4 days after infection with 1918 flu than are found with the Texas virus. All mice died within 6 days of infection with 1918 flu; none died from the Texas strain.

The concern

Not surprisingly, many people are concerned about this revelation. They've pointed out that the group has made what is possibly the ideal bioterrorist agent: deadly and highly transmissible. Tumpey et al. counter back that significant precautions were taken, and remain in place regarding storage and handling of the virus. We also need to remember the old causation triangle:

Though the agent may be the same, the host and the environment are much different. The population in 1918 may have been mostly naive to H1N1 serotype viruses, but the current population is not. Indeed, there's an H1N1 serotype virus in the vaccine forumlation for 2005-6, and similar viruses have been used for years. Viruses of this serotype have been circulating for decades, so much of the population should have at least a partial immunity to the 1918 virus. Additionally, one change in the greater "environment" is the production of antiviral drugs. Tamiflu has already been shown to be effective against the 1918 virus. As I mentioned yesterday, the 2 influenza models published showed that Tamiflu could be used to halt the spread of a pandemic virus, if it's given soon enough and if the R0 is low enough. If there is an intentional release by terrorists, or an accidental release due to a lab accident, there should be enough time to isolate cases and provide Tamiflu before it turns into an epidemic situation. Finally, as the 1918 virus isn't out there circulating (and, therefore, evolving) in nature, a "just in case" vaccine could be made. Given the fact that we have a virus out there that is similar in many ways to the 1918 virus, I think the potential benefits outweigh the possible risks at this point in time. I just hope they don't prove me wrong.

Other posts in the series:

Day 1: History of Pandemic Influenza.

Day 2: Our adventures with avian flu.

Day 3: Challenges to pandemic preparedness

More resources on pandemic influenza: